'Design Is a Profession With Responsibility'

Lucas, could you tell us a bit about your path to becoming a designer?

I studied classical product design and graduated around 20 years ago. My portfolio included projects like a radio for a car, a door handle – things like that; product design as it used to be. But then I realised that the ideas I wanted to develop weren’t really industrialised or connected to traditional products or industry. So I set up an atelier with a friend, where we conceived, created, and produced our own projects while learning craft in a DIY way.

After seven years, I moved to Eindhoven and started again from scratch. My time there feels like the halfway point in my professional life. At almost 30, I began a two-year Master’s in Eindhoven; for the past five years, I have been back in Madrid. Most of my recent projects are coming from here, which is very practical – and it fits my practice well. Whenever possible, I like to work and produce locally.

You work in very different fields. How does your approach differ when working on a space compared to creating an object or an exhibition?

There isn’t really a fixed method, but the context is clearer when working on a space than on an object. I see a space like a big object you work from the inside. For the Venice Biennale, we made two columns almost five metres tall – massive objects. With both objects and spaces, I try to limit possibilities by setting rules for myself. It’s like games: the more rules, the more fun.

What kind of rules?

I ask myself questions like: How much can I learn about the materials – their origin or environmental footprint – before they reach me? How can I involve local people? How can I avoid buying new things? These rules make the process engaging and guide decisions so that none break these principles.

With objects, it’s similar. Can I simplify it? Can I make it somehow rawer? Sometimes it takes a whole month to find one simple, tiny, almost silly solution – after trying out several others.

Your work challenges conventional notions of furniture by opening up new ways of engaging with materials and redefining how objects take form.

I believe rules set boundaries. For example, a chair must be something to sit on, and materials need to stay in place to be recycled. So I set simple constraints, and within those, my design choices unfold. I need this material to stay here and not go away. If it goes away, I know it’s never going to be recycled. That’s why I must find a way to ensure it stays. Once the constraints are set, the design possibilities become defined. It has to be this way. With all these constraints in place, there is only a certain scope of design available. Take the wall we made for the Sancal offices: it was built from old flooring that was going to be thrown away. Due to its thin aluminium layer, it reflects sunlight when positioned by windows, brightening the space. If I had bought new materials, it would have been expensive. Instead, I used free, reclaimed materials and paid local workers, rather than buying from an overseas company’s catalogue.

How do you start your design process?

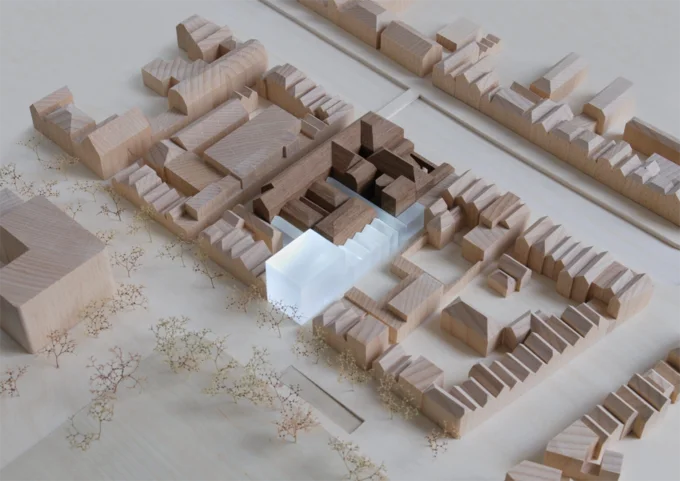

I’m a craftsman, so I prototype a lot. I work with models a lot. I begin with a prototype of a finish or a first unit – for example, part of a chair or lamp. From there, the composition evolves, usually very collaboratively with clients. And I don’t do visualisations because I can’t know how it will look until I open the wall or floor, or classify the materials we have in the space. That’s my way of working so far.

What’s your take on furniture? Is it sculpture, utility – or something else entirely?

I mean, I come from design. Design is a profession with responsibility – towards materials, construction, nature, and social interaction. It goes beyond aesthetics. I try to make functional objects, maybe artistic functional objects. For instance, if you take the dead fluorescent tubes we used as lamp shades at Mo de Movimiento: they emit light – so they are lamps, sculptural perhaps, but functional nevertheless. Ultimately, I aim for functional solutions.

Your recent office space for Mo de Movimiento in Madrid stood out for its radical material reuse. How did the client like the idea?

The communication of my work has grown naturally over the past 20 years. And that brings a very specific client already, with a very specific openness and a certain carte blanche, which is not very common. It’s less about isolated projects and individual clients, and more about an ongoing, collaborative body of exploratory work. And in some projects, I repeat certain findings from others, because I encounter the same problem – fluorescent tubes, for instance.

Your project for Sancal's showroom in Madrid also took an unconventional approach. Old floor panels became light reflectors, floor supports turned into wardrobes, and neon tubes became a sculptural centrepiece. When do you decide if something becomes furniture or a wall covering?

Fluorescent tubes are still light tubes. I find them beautiful objects per se. And they are absolutely not recyclable. You bring them to the hardware store, they put them in a cardboard box, and they go to a safe destruction area. The glass is very thin, so it will never become glass again. The aluminium is very thin, so it will never become aluminium again. It's simply destroyed safely. So it should never leave the space. For the restaurant Mo de Movimiento, I reinterpreted them as a lamp, knowing this was a material too valuable to discard. We repeated this process at the Sancal offices. In this project, we also managed to transform a lot of material that we had previously identified as non-recyclable. For us, this was the starting point: What would happen to everything here if it were thrown away? Any material that cannot be revalued must be kept in a creative way. This is our challenge.

This year, you took over an entire room at the Spanish Pavilion of the Venice Architecture Biennale. Could you tell us more about the concept behind it?

It was quite a surprise to be invited, as I’m not an architect. But it shows the value of transdisciplinary work. We created an installation with two massive iconic columns. Somehow they are objects of curiosity. So what we did was go into the metropolitan area of Madrid and documented features from the buildings from the 18th to 20th century – structuresnow protected as part of the city’s identity. At the same time, we’re questioning what happens to building residues, especially from the poorly built post-war housing of the 50s–70s, which we now see as a kind of geological layer. Instead of viewing this as waste, we’re suggesting it can be reused – transformed from residue into, for instance, ornament – becoming part of our new architecture and our cities’ identity. If we value that material, we preserve it longer, and that’s the heart of what we were saying with the pavilion: residues, too, can become something beautiful and lasting.

Interiors are intensely used, short-lived, and trend-focused. How do you navigate that contradiction – designing something meant to last in a world that rarely lets it?

That's something I cannot totally control. I hope that they become long-lasting, of course. But I cannot know. I have to work with this contradiction present. Thus one of my rules is: If I receive a problem, the following person should receive the same problem. So if I receive a problem that is fibre encapsulated in a plaster, then I can only use fiber or plaster to work towards the solution. Somehow, the description of the materials, as in a painting or a museum sculpture, must remain unchanged once I have worked with them. If I add something, it should be something that can be removed. I am passing on the same problem that I encountered to the next person involved in the future rehabilitation of the space. It's important to keep in mind that the configuration of materials you create as a designer now will become someone else's problem in the future.

And every space has a different materiality.

Yes! That makes it very, very unique. It‘s something that cannot be repeated. I can't build another Sancal office in the same way somewhere else because I won't have access to the same materials. We work by mining the spaces.

I think it's important that in general, we should try to frame all of this in the most positive way. We're not doing this to save material. We're not doing this because of the global climatic crisis. We're doing this because there's a huge creative opportunity behind it that is connected to the identity of the very local – its past and future. And we are doing this because it becomes more significant and relevant as a creative and material effort. It has a story drawn from its experience, and it goes through a transformation, which is interesting. If this is the starting point, then the whole project creates a different dialogue with us as users, human beings and inhabitants of this planet.